25 January 2022

The COP26 gathering in Glasgow last November refocused attention on the fragile state of the planet, and the urgency of reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2050.

It’s safe to say that goal won’t be reached without changing the way we live. Older urban landscapes, with their energy-intensive buildings and congested roadways, will have to be completely reinvented. Lockdown living has prompted deeper thinking about what people want from their homes and workplaces and, as a result, the construction sector can expect clearer direction from tenants and landlords as to what smart cities will look like.

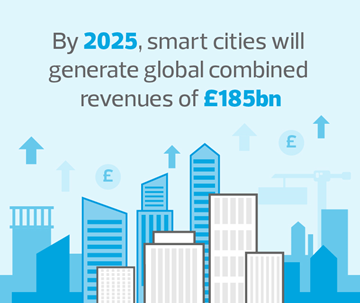

Quite literally, the construction industry will be building the world of the future, presenting exciting opportunities for growth and innovation. By 2025, the projected revenue of the smart city market worldwide will be $185bn, over half of which will be from smart infrastructure and the smart city building market.

But is the sector ready to make the most of them and deliver the smart cities of the future?

That was then, this is now

The stereotype of the construction sector is that it’s not particularly progressive. Owner-operated firms can turn profits in the tens of millions but aren’t necessarily run as big businesses. Instead, ‘this is the way we’ve always done things’ has become a standard mindset in some parts of the industry.

Compounding the problem is that a reluctance to share information has led to a lack of collaboration and hampered sector-wide development. This stems partly from commercial sensitivities, but often it’s because construction data is stored inefficiently, meaning it isn’t always readily to hand when needed. Building information models (BIMs), for example, are filled with data that many different stakeholders can access. A recurring issue is deciding who ultimately has ownership and responsibility for the data.

But these old ways of working all need to evolve in the face of coronavirus, advances in data management technology, tougher environmental standards, and changing consumer demand.

Smart construction requires collaboration

Historically, the delivery of a project brings a fragmented supply chain together to deliver individual stages of a build in line with the initial design. Undoubtedly the biggest change we are seeing, and will continue to experience, is the industry bringing together the machine, technology, and people through each stage of design, procurement, delivery and after-life care.

At the project design stage, cloud technology can connect and improve the supply chain by:

- allowing shared access to design and data for the project;

- easing the flow of delivery at each stage by removing fragmentation; and

- increasing productivity through collaborative learning.

The design of smart buildings and the repurposing of old stock to become smart buildings will create data that’s accessible to the industry through open platforms, including the after-life care to further foster that essential collaborative environment needed for industry wide innovation.

The construction industry is key to the success of smart cities. It is responsible for designing smart assets in collaboration with the user’s specifications, including meeting ESG targets and generating real data from those assets. In a true smart construction environment, everyone will have access to the data needed to understand a building’s design, composition and live activity.

The human factor

Good intentions are no good without the right skills in the workforce to make them a reality. The uncomfortable truth is that, right now, the UK has neither the data skills nor, in some areas, the right tools needed to create and maintain smart cities.

As always, recruitment and training remain an essential part of bridging these gaps. Digital skills and training must be made available across all areas of construction businesses. Because of the fast pace of change, businesses should constantly be assessing what ‘skilled’ labour will look like in ten years’ time. This includes an evaluation of the skills and experience needed in the boardroom, as firms who allow themselves to fall behind will be left playing an impossible game of catch-up.

New ways of thinking about how cities should serve those who live in them are also needed – wherever possible, consumer convenience should be at the forefront. This includes ‘hub and spoke’ models, otherwise known as ‘15-minute neighbourhoods’, that encourage more cycling and walking.

Ultimately, the move to smart cities will be driven not by AI or other technologies, but by people. A focus on consumers and their needs will be what constructs the smart cities of the future.