16 March 2023

Trust is the lubricant that makes modern commerce possible. It facilitates an uninterrupted operation of finance that allows businesses to fund expansion and modern economies to operate efficiently. It reduces transaction costs, minimises frictions and creates the conditions for broader and deeper forms of contracting and economic interaction.

Ask yourself this question: when asked if you want a receipt at the supermarket, or when conducting a transaction on a mobile device, what’s your answer?

Most say - “no thanks”.

And why?

Trust in the system.

Evolving financial conditions and key risk metrics imply that under current conditions trust is eroding as concerns about counterparty risk multiply. Indications are that private sector financial institutions are pulling back from lending.

Measuring risk

The fragile nature of trust and modern finance means we follow a number of metrics to gauge risk in the system. One of those is the RSM UK Financial Conditions Index.

As of Thursday morning, the index sits at almost one standard deviation below neutral, indicating increases in volatility and risk priced into financial assets, with the prospect of diminished investment and economic growth in coming quarters.

Global financial markets are attempting to come to terms with the result of relaxed oversight of the global banking industry, the vulnerability of small and medium sized banks with exposure to interest-rate risk and the bursting of the crypto-currency and tech bubbles (on Tuesday morning, Meta announced intentions to cut 15,000 jobs).

The collapse over the weekend of a third regional US bank and concerns of contagion in Europe, especially around Credit Suisse, are the immediate cause of a reassessment of risk in the equity and money markets. That spilled over into the bond market, where a shift in expectations regarding economic growth precipitated a drop in both 2-year and 10-year bond yields.

The presence of instability in the money markets is particularly distressing for the business community.

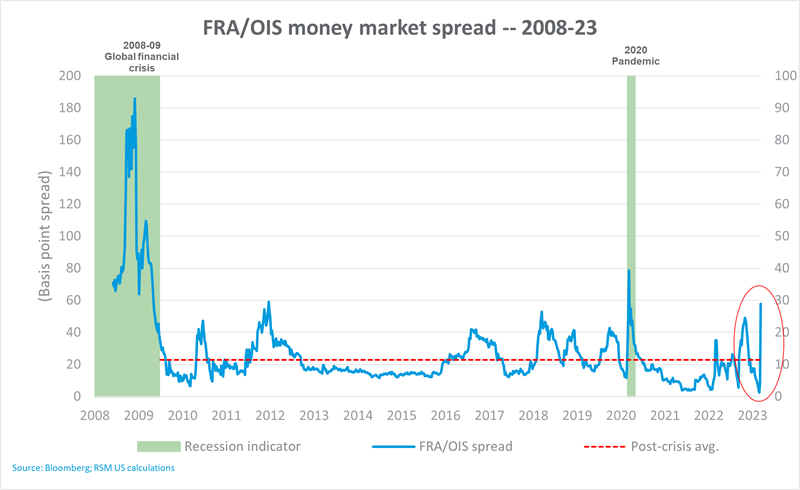

Another metric we follow that reflects basic counterparty risk, and our preferred barometer of trust within the banking system, is the spread between the Forward Rate Agreement and the Overnight Index Swap or FRA/OIS.

A forward rate agreement is a transaction that swaps future fixed interest payments for variable ones. Whereas the overnight index swap is derived from contracts in which investors swap fixed and floating rate cash flows.

A key rate for UK and global rates is the sterling overnight index average rate (SONIA), which is the benchmark that underscores interest rates on trillions of dollars of financial instruments such as credit cards, auto loans and mortgages.

That spread has increased notably in recent days and now reflects a 57-basis point difference, which is up from a near zero readings just days ago. While nowhere near 2008 levels - this is not yet a 2008 type of crisis - it is approaching levels observed during the pandemic era.

While the sharp increase in the FRA/OIS spread signals increased expectations of risk, volatility in short-term credit spreads signals uncertainty regarding economic growth and the availability of short-term loans that permit day-to-day business operations. All of these are consistent with growing counterparty risk which could make interbank lending riskier. Since banks would take losses if other banks fail or were seized they will demand higher interest rate payments to lend to one another which causes an increase in the FRA/OIS spread.

How do we move forward?

In past episodes of financial stress, distress in the money markets has forced the central banks to become the lenders of last resort, providing liquidity and avoiding a commercial market freeze-up.

That is what the authorities in the US and UK did over the weekend by shoring up trust and confidence within the domestic banking system by providing an implicit guarantee of all deposits.

Should the problems inside the EU banking system expand, we expect that European and Swiss monetary authorities will take whatever action necessary to put a floor under their financial system.

The central banks have to strike a careful balance between the need to restore price stability and re-establishing the financial stability that characterised the current moment.

Do they risk allowing inflation to continue, which would hurt the general public and the economy? Or do they regard the bursting of asset bubbles a greater risk to the financial health and functioning of the economy?

Even before the events of the past few days, it had become difficult to dissect market actions. While the markets have consistently discounted the Fed and ECB’s intentions to combat inflation, the markets have taken notice of the potential of failure of banks seriously.

It's a matter of trust.