Manufacturers in the UK are still feeling the hangover from the initial wave of coronavirus-related shutdowns of factories and ports during 2020 and 2021. And with the ongoing shutdowns in China, yet another supply chain crisis is threatening to hit later this year.

If that wasn’t enough to cause chaos, the war in Ukraine has forced commodity prices – such as metals, energy and agriculturals – to skyrocket. This has increased costs for manufacturers and is making it more difficult to get access to raw materials.

With that in mind, it’s unsurprising that the manufacturing sector is the worst-performing major part of the UK economy. Its output is only 0.1 per cent above pre-pandemic levels. That compares poorly to the construction sector, where output is 4.1 per cent above its pandemic level, and the services sector which is 1.9 per cent above.

It will take time for the impact of many of these factors to be felt in the sector, but it will eventually lead to considerable disruption. It’s unlikely the manufacturing industry will catch up with its peers in construction and services until late in 2023.

So how bad have things got?

In The Real Economy’s topical survey exploring the current state of global supply chains, only 39 per cent of middle market business leaders had experienced disruption within their supply chains over the past year. This statistic may raise eyebrows in boardrooms across the manufacturing industry, but the results reflect that, of the 412 respondents, many have come from sector’s far less impacted by global supply chain issues. The nature of what manufacturers do has meant that the sector has borne the brunt of many of the issues caused by the pandemic, Brexit and now the war in Ukraine.

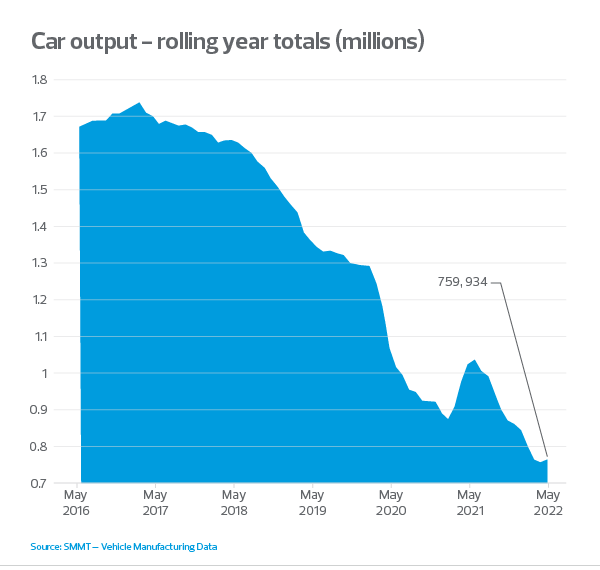

The extent of this pressure is most clearly visible in the automotive industry. In 2019, the UK automotive manufacturing sector produced 1,303,135 cars. By the close of 2021, that number had shrunk by 34.7 per cent to 850,575. This is in part due to the global shortage of the essential semi-conductor parts that are required in modern vehicles. The shortages have severely hampered production levels since April 2021 which saw just over 68,000 cars produced in the UK during that month. Since then, things have got steadily worse, with the latest production figures for May 2022 representing a 46 per cent decrease in the number of cars produced during the same month in 2019. Now, with the semi-conductor shortages and further complications caused by the war in Ukraine, automotive manufacturers are braced for yet more pressure, both within the UK and across the globe.

Delivery times – stable, but not improving

Another indication of the continuing problems for manufacturers are delivery times. The suppliers' delivery times index from IHS Markit's PMI business survey asks purchasing managers if it is taking their suppliers more or less time to provide inputs to their factories on average. In October 2021, purchasing managers indicated that delivery times had not been as bad since April 2020 during the first lockdown, which remains the worst on record. Timings have gradually improved since, but now we are seeing a levelling off of those improvements, meaning firms are still waiting considerably longer for deliveries than they were before the pandemic began.

Margins squeezed for two straight years

These global supply chain issues have not just resulted in increased time waiting for deliveries from suppliers. They have also had huge ramifications on the costs of goods bought and sold by manufacturing businesses. The lack of availability of key components, materials and ingredients continues to drive up input costs. Inevitably this has had a knock-on impact on consumers in the form of increased output prices.

For all those businesses that confirmed they had experienced supply chain disruption, our survey of the middle market showed 46 per cent had seen an increase in costs within their supply chain. Again, this figure seems low when considering the manufacturing sector’s plight and the Producer Price Inflation Index confirms this. Producer input prices rose by 24.0 per cent in the year to June 2022, this is the highest the rate has been since records began in January 1985. Producer output (factory gate) prices rose by 16.5 per cent in the year to June 2022. This shows just how challenging an environment manufacturers continue to operate in with margins being squeezed for such an extended period. As a result, regular communication across suppliers and customers has never been more important.

What happens next?

The next year is unlikely to bring much relief for the manufacturing sector. Supply chain challenges will remain for at least another year, preventing a ramping up of production. What’s more, a weakening global economy will start to eat into demand, especially as rocketing inflation forces consumers to choose between essentials and luxury goods. There are already signs of a decline in both the new orders index and the future output index, suggesting that output will deteriorate over the next few months.

The recent coronavirus related shutdown of many factories and ports has led to a decline in the number of shipping containers travelling from Asia to Europe for the last three consecutive months, they were down by 8.5 per cent y/y in April. On top of this, the value of UK imports from China had fallen by 20 per cent y/y in April.

China has shown very little willingness to ease its ‘zero Covid’ strategy, which increases the chances of future shutdowns even once the current wave has passed, already we have seen a 20 per cent y/y fall in UK imports from China as of April. What’s more, there is no sign of the war in Ukraine easing. Imports to the UK from Russia had fallen by 60 per cent y/y in April and most likely will continue to fall in the coming months.

It will take some time for the impact of this drop in imports to be felt across the manufacturing sector and there is some evidence that businesses have partially adapted to supply chain issues. But supply chains are likely to come under renewed pressure again later in the summer as the drop in imports from China and Russia feeds through. Even once China is fully reopened again, there is likely to be another jump in shipping prices, which are still highly elevated, as global businesses compete for capacity.

Time to re-shore?

Sterling weakness, input cost inflation and disrupted supply chains has led to increased interest in the option of ‘repatriating’ offshore manufacturing, or re-shoring to the UK. For many sectors this will be a significant top up of reserve capability and capacity alongside their existing supply chain, and for others possibly a complete replacement. In engineering, a collaboration between nearly forty trade bodies, media companies and academic and technical associations has set up a website called Reshoring UK. Significant collaborators include the University of Warwick, Catapult, the Manufacturing Technology Centre and Innovate UK. The purpose is to connect manufacturers with accredited suppliers in a structured process and encourage engagement with suppliers of UK-sourced engineered products. For many, reshoring is now seen as an increasingly important supply chain strategy, but it is not the only option. One thing is for certain, business leaders in the manufacturing industry must future proof supply chains given the turbulent times ahead

The Real Economy