10 March 2022

Economic conditions will remain challenging for manufacturing firms over the next 12 months at least. Surging commodity prices and sanctions on Russia risk reigniting supply chain disruptions, which have hindered production over the last two years. Underlying demand for goods remains strong for now, but soaring inflation and the biggest squeeze on real incomes on record will drag on consumer spending in the second half of this year.

Supply shortages, surging material prices and difficulty in hiring qualified staff have stalled the manufacturing sector’s recovery. Indeed, output in the sector hasn’t risen since April.

A shortage of raw materials is a problem across the industry, and the impact is most obvious in the automotive sector, where a lack of semiconductor chips has meant that output is still about 17 per cent lower than it was in February 2020, before the pandemic.

Input costs surging

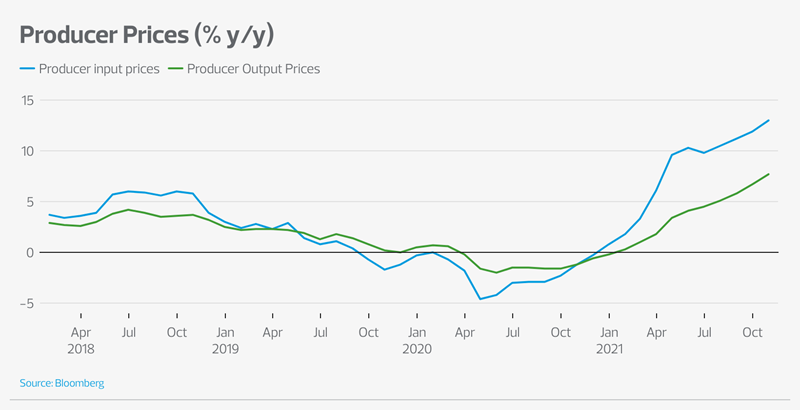

The manufacturing sector was already being hit especially hard by the surging cost of raw materials. Producer input price inflation, which measures how much manufacturers are paying for inputs, has risen from just 1.8 per cent year on year in January 2021 to 13.6 per cent in January 2022.

The recent surge in energy and fuel prices, with oil prices over $125pb and the price of natural gas at about £5.60 per therm, dwarfing the £4.50 level reached in December, will quickly feed through into sharply higher costs for manufacturing firms.

What’s more, over the next six to 12 months the surge in the prices of agricultural commodities and many base metals will feed through into higher prices for everything from raw materials to intermediate goods. This will almost certainly bring input prices inflation worryingly close to the 20 per cent increase in costs that, in our survey with Make UK, the majority of manufacturers said would have serious consequences for their businesses.

Manufacturers starting to pass on costs

However, manufacturers have been able to pass on an increasing portion of these costs. Producer output price inflation, which measures the prices of goods leaving factory gates, has risen from 0.3 per cent year on year in January 2021 to 9.6 per cent in January 2022. That suggests that the impact on manufacturing firms’ profitability probably isn’t as bad as the surge in costs implies.

Supply chain crisis part two

The best example of how the crisis might spark another supply chain crunch is in the palladium market, where Russia’s share of the global production is just over 45 per cent. Palladium is used to produce the advanced microchips used in vehicle production, so this will impact manufacturing firms (especially in the automotive sector). But Russia is a major producer of many raw materials and more niche products. As a result, all middle market manufacturers should be prepared to scour their downstream supply chains for areas that may be vulnerable to supply disruptions from Russia.

The good news is that the manufacturing sector is ramping up investment in response to the shortages of labour and materials and the changing economy. Investment was 2.3 per cent higher than before the pandemic in Q3 2021. Stronger investment should feed through into higher productivity, which, in turn, should result in more competitiveness and profitability. It is particularly encouraging to see investment above pre-pandemic levels given the cashflow issues being felt by many across the sector.

Demand will suffer

As well as pushing up business’s costs, surging inflation will damage consumer spending. Admittedly, household’s balance sheets are robust with household’s sitting on a pile of excess savings worth around £250bn (over 10 per cent GDP). This will provide some insulation against rising prices. However, it seems inevitable that consumer spending will take a hit. We have recently revised down our forecast for GDP growth in 2022 by 1ppt to 3.5 per cent. And if oil prices rise to around $150pb and stay there for any length of time, there is a risk of returning to recession in Europe and the UK.

Interest rates will rise, but not by much

Many manufacturing firms have accumulated significant amounts of debt during the pandemic and are concerned about the impact of interest rises on their ability to service that debt and to borrow to invest. Indeed, the Bank of England has strongly hinted that interest rates will continue to rise in the next few months and financial markets are expecting interest rates to rise from 0.5 per cent to 2.0 per cent by the end of 2022.

The crisis in Ukraine and the sanctions on Russia have thrown the outlook for interest rates into disarray as the Bank of England will have to weigh the surge in inflation against significantly lower economic growth. But there are still two key points worth making. The first is that interest rates will rise only gradually, and they will remain very low by historical standards. Secondly, and more importantly, real interest rates, which take inflation into account, will remain negative for a long time yet. This will create fertile conditions for manufacturing firms to invest in the productivity-enhancing technology needed to survive and thrive in the ultra-competitive post-pandemic economy